Queer Memory in Precarious Times

Exploring how our personal histories shape collective memory and why preserving queer ephemera is a radical and necessary act

Hi Friends,

Kicking off this newsletter with a huge welcome to all my new subscribers! I’m blown away that over 3,000 of you have signed up to read my words and support this project. I’m so excited to keep building this community with you. Thank you for being here <3

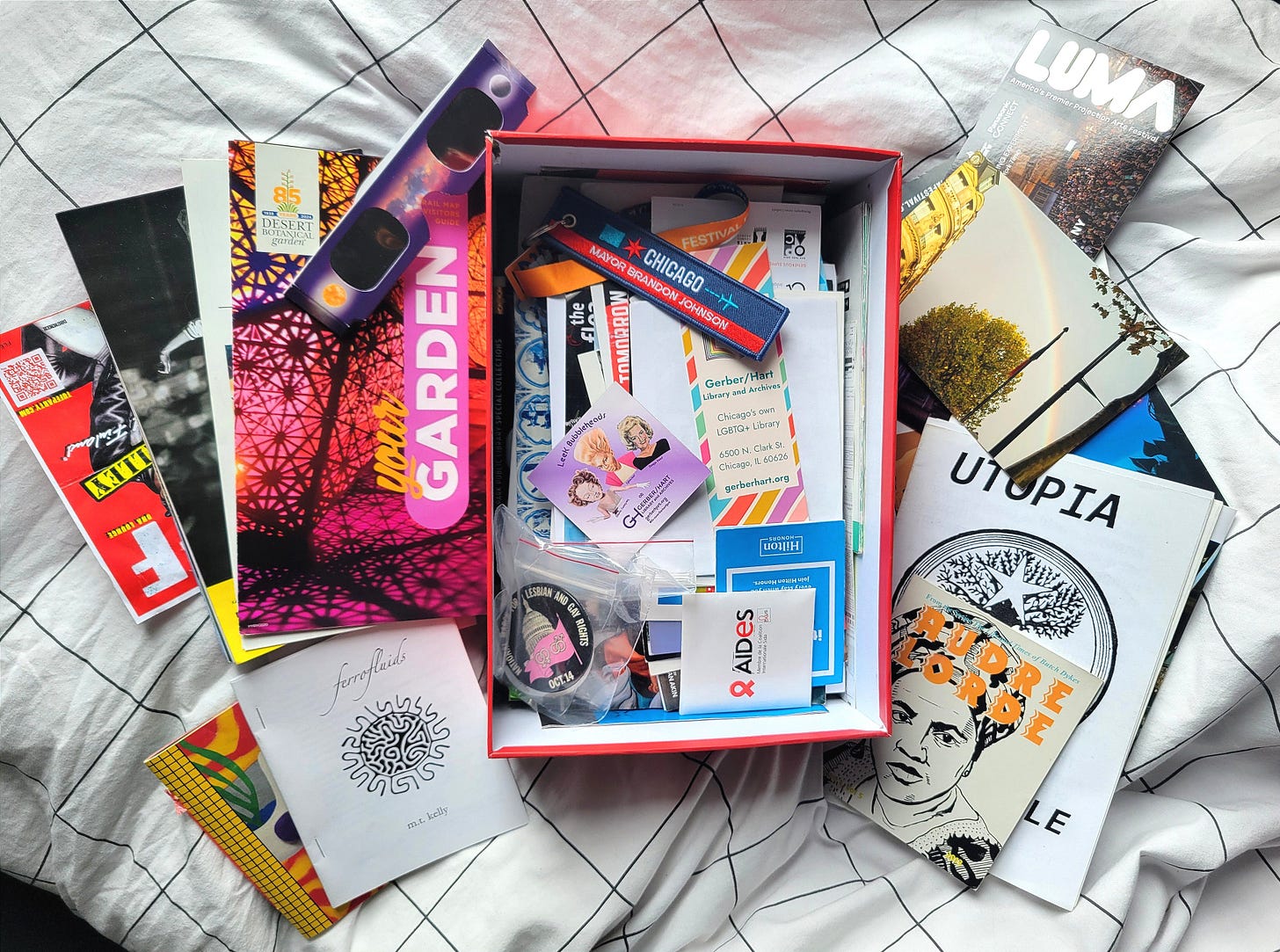

This time around, I’m talking queer ephemera, Barney Live! In New York City on VHS, and the necessary art of memory-keeping. Looking back on the objects I’ve kept over the years, I see them as early signs of a queer impulse to document and preserve the traces of queer becoming, forming the foundation of my work in archiving queer history. This piece explores how personal histories shape collective memory and why preserving queer ephemera, no matter how small or silly it may seem, is a radical and necessary act.

Announcements!

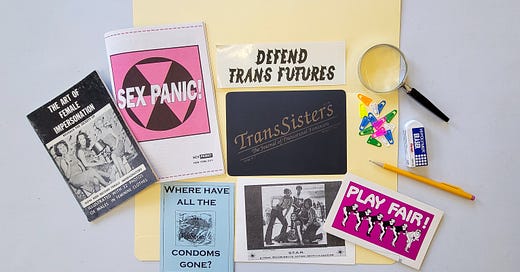

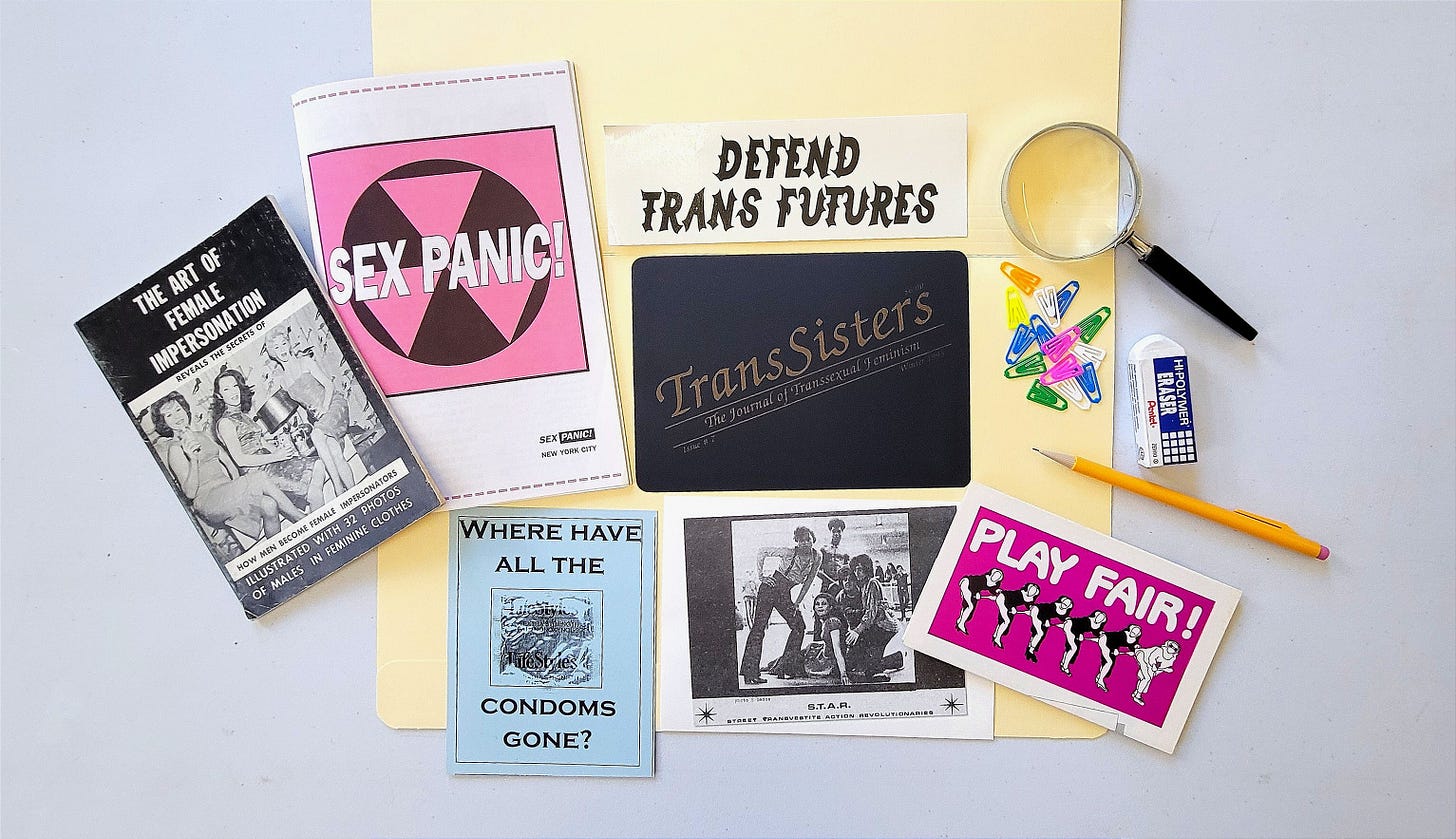

I'm launching Queer Pages!, a new series on Queer Archive Fever exploring the rich legacy of queer printed media—zines, periodicals, posters, flyers, and other DIY ephemera that have kept our communities informed, connected, and empowered. Subscribe to get the inaugural post delivered straight to your inbox!

Read my last post, titled “Blueprints for Survival: Zines, Self-Publishing, and Community Building” where I discuss how zine-making and self-publishing can be powerful tools for survival, helping us reclaim autonomy, build community and resist control in an age of digital surveillance.

Zines! I’m currently working on a few zines that I can’t wait to share with you all. More soon!

— Queer Archivist

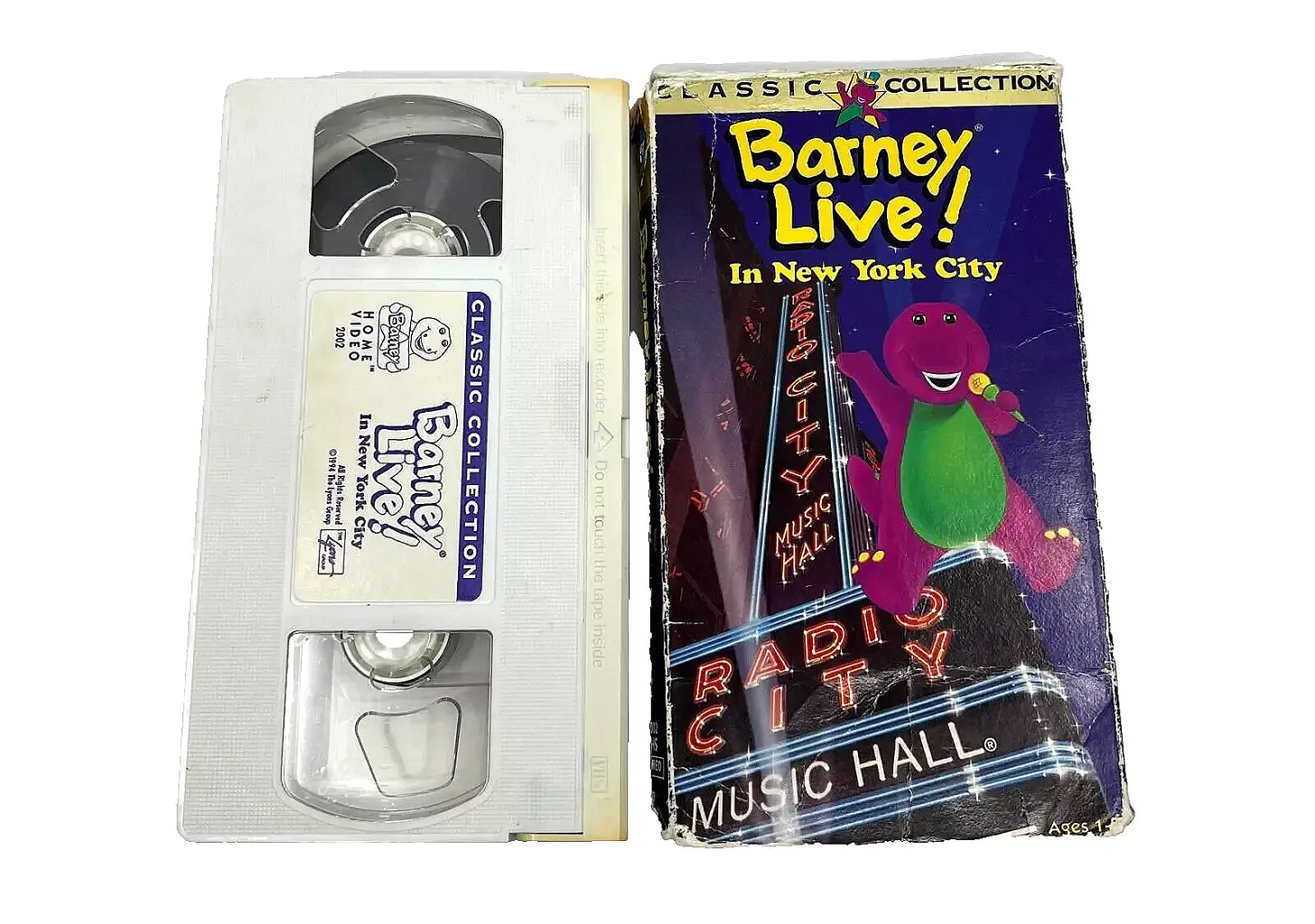

Growing up, I struggled to let go of objects I collected. Mostly books, VHS tapes, clothing, and small keepsakes that felt too important to discard as time and space moved on. Among these objects was a Barney Live! In New York City (1994) VHS tape, its bright white plastic outer shell standing out in my memory like a relic of a time period that I refused to part with. I watched it more times than I’m comfortable admitting on the internet.

I never saw the stage production live, but that didn’t matter. The tape was a portal back to the South Bronx apartment I grew up in. Watching it on my chunky TV with the built-in VHS player became its own kind of ritual. Even as I outgrew Barney, I held onto that tape far longer than I probably should have, reluctant to let go of something that felt so familiar, so fixed in time.

And while neither Barney nor the tape itself was inherently queer (I’ll let y’all argue about that in the comments), the impulse behind holding onto it—the deep emotional tether to something safe, familiar, and laced with personal history—mirrors how queer people have long preserved queer memory through collecting objects and ephemera. I wasn’t just collecting random objects; I was curating, safeguarding what felt significant before I had the language to name why.

At the time, I didn’t think of it as memory-keeping, I just knew I wanted to hold onto things that felt important to me. Years later, in graduate school, I encountered Ann Cvetkovich’s An Archive of Feelings1, and suddenly, that childhood instinct to preserve memory felt like part of something much larger. In this seminal work, she writes, “In insisting on the value of apparently marginal or ephemeral materials, the collectors of gay and lesbian archives propose that affects-associated with nostalgia, personal memory, fantasy, and trauma—make a document significant.” Her words unlocked something in me. Archiving was never just about preserving “official” records with arbitrarily sanctioned historical value—it could and should be affective, political, and queer. A practice shaped not by institutional authority but by the pulse of lived experience, by the insistence that queer memory matters even when it exists in the margins. This realization has since become a foundation of my own archival practice, guiding how I approach queer memory-keeping as resistance.

A Legacy of Lesbian Memory

Cvetkovich goes on to highlight the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA) as a radical example of documenting the ephemeral, the affective, and the deeply personal dimensions of lesbian life. She describes how the archive prioritizes collecting materials that might otherwise be discarded—love letters, T-shirts, bar flyers, diaries—and how this refusal to separate history from emotion disrupts traditional archival norms. She writes,

“The Lesbian Herstory Archives, and others like it, [have] been established from below in an effort to demonstrate that lesbianism has a history and to save materials that might otherwise be destroyed either because of overt hostility or ignorance. And in order to make erotic feelings the subject of archival history, the Lesbian Herstory Archives collects letters, diaries, flyers, and other ephemeral materials that might seem personal or private.”

These intimate traces of everyday queer life hold as much historical weight as any institutional record. They insist that memory is not just what survives in official documents, but what lingers in the personal, the private, the nearly lost.

This ethos is beautifully captured in The Archivettes, a documentary that follows some of the incredible volunteers that steward the collections at the Lesbian Herstory Archives. Through their work, we see how deeply personal the act of donating to an archive can be—how it’s not just about handing over objects, but about entrusting memories, relationships, and fragments of oneself to a collective queer history.

Liz Sullivan2, an audiovisual archivist-in-training and regular volunteer at LHA, reflects on this in her piece Tales of a Community Archivist: Collection Pick-Ups. She writes about the affective experience of doing collection pick-ups from lesbian elders—many of whom are donating their materials as they prepare to move into retirement communities, assisted living facilities, or are planning as they are nearing the end of their lives. “Anxious about finding a place to house their materials, given that artifacts of Lesbian life and existence have been historically hidden away, disregarded, or destroyed,” these donors entrust their histories to the archive, hoping their life’s work will not be forgotten. Liz describes these moments of connecting with lesbian elders as some of “the most profound experiences” in her work.

The radical nature of LHA’s archival practice lies in its refusal to impose hierarchies of value. As Liz explains, “We resist the canonization of figures and want to make visible multiply-marginalized Lesbians and histories that may not be represented in academic research archives… LHA takes all materials relating to Lesbian existence.” She humorously captures the ethos of queer community archiving: “We often joke that our accessioning policy is, ‘If a Lesbian has touched it and wants it in the archive, we’ll take it.’”

Queer memory-keeping has always been shaped by these affective ties, by a refusal to let go of what the world might deem insignificant. And in a time when queer histories are being actively targeted—through book bans, the criminalization of LGBTQ+ education, the shuttering of community archives, and disappearing community spaces—the act of holding on becomes an act of defiance.

Queer Memory in Precarious Times

In 2023, Florida’s Board of Education expanded its censorship of LGBTQ+ history, removing books and resources that acknowledged queer lives. Around the same time, Missouri lawmakers attempted to defund public libraries, citing their “controversial” collections3. These attacks are not isolated—they are part of a long history of erasure, where those in power attempt to control whose stories are told and whose histories are buried.

This trend has continued unabated. In January 2025, the U.S. Education Department under the Trump administration dismissed 11 complaints concerning book bans imposed by local school districts during the previous administration4. Advocacy groups like PEN America reported over 10,000 book bans in public schools during the 2023-24 academic year, disproportionately targeting works by authors of color, LGBTQ+ writers, and women—often those addressing issues like racism, sexuality, gender, and history.

In the face of this erasure, archiving is not a neutral act. It is an act of resistance. For queer and trans communities, memory-keeping is survival. It is a way to assert our existence against forces that seek to make us invisible. Archiving is not just about collecting and preserving the past; it is a radical insistence that our lives, our struggles, and our joy matter—not just then, not just now, but always.

Much of my thinking on this has been shaped by scholars and activists who understand archives not just as static repositories of memory, but as active tools of resistance and futurity—holding space for what has been while daring to insist on what is still possible.

Queer Archival Practice as Resistance

Queer history is often found in what lingers—the traces, the gestures, the ephemera that resist permanence but still carry deep meaning. As José Esteban Muñoz writes in Cruising Utopia5, “The ephemeral does not equal unimportance; rather, it is one of the ways in which queer culture exists in the world. It is a mode of being that insists on the potentiality of the moment and the futurity of the gesture.” In other words, queer ephemera are not simply things left behind; they are evidence of queer life in motion, blueprints for what’s to come, proof that we have always been here and will continue to be.

“Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future. The future is queerness's domain.”

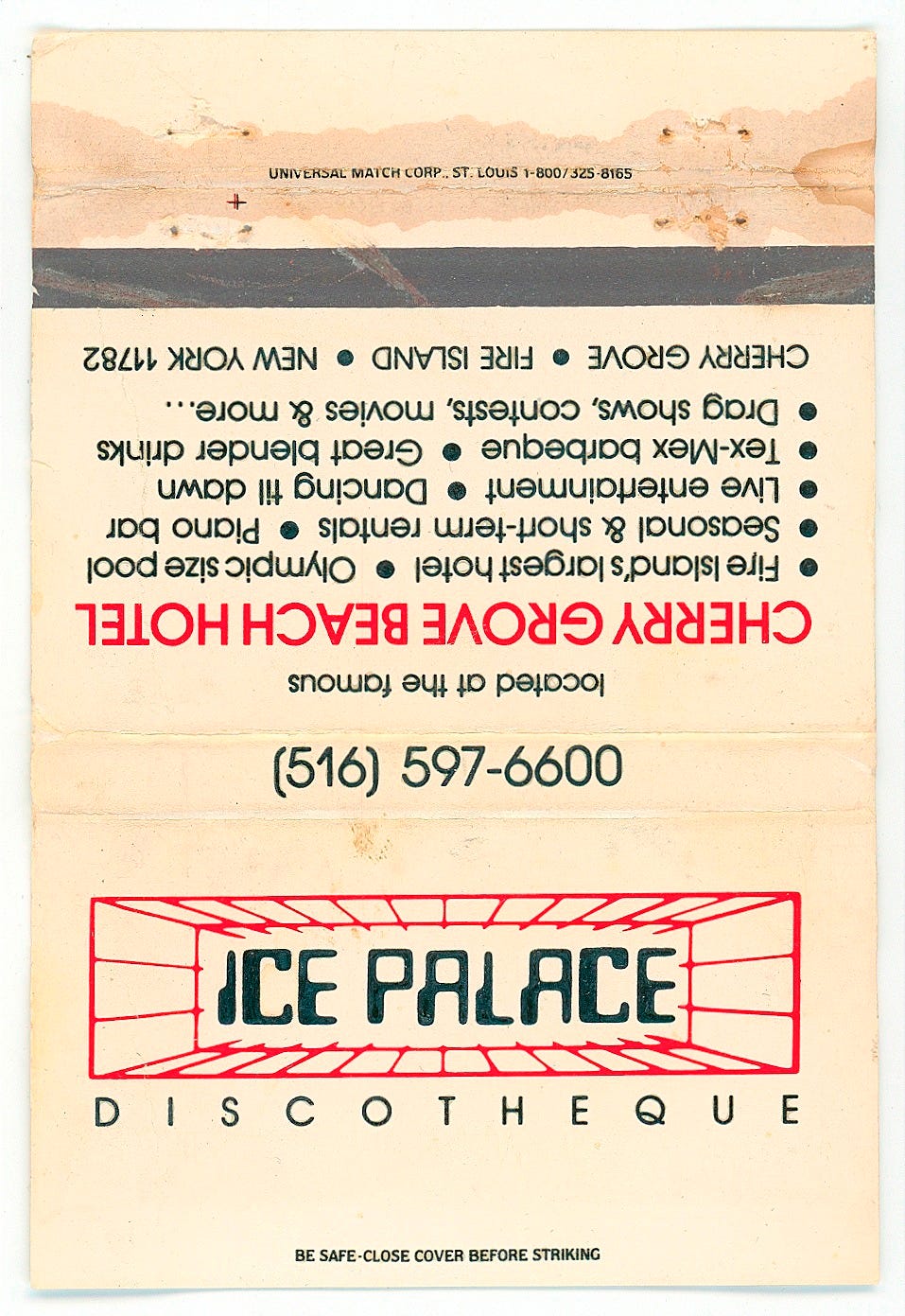

Queer ephemera—matchbooks stamped with the names of long-gone gay bars, ticket stubs from a drag show, protest signs hastily scrawled before a march, voicemail tapes saved long after a lover has left—are fleeting by design. Made for a specific moment, they were never meant to be permanent artifacts. And yet, they become powerful records of queer ephemeral acts. These objects carry the residue of queer life, proof that we were here, that we gathered, that we built spaces for ourselves even when the world refused us permanence. Traditional archives often overlook these materials, dismissing them as too impermanent or insignificant, but their very impermanence is what makes them so vital.

To collect and preserve queer ephemera is to push against disappearance. It is to say that our histories deserve to be remembered, not just in grand narratives, but in the everyday objects that carried us through. These archives, whether housed in institutions or assembled in personal collections, are acts of defiance—gestures of care, of survival, of refusing to let go.

DIY Memory-Keeping vs. Institutional Archives

Traditional archives tend to privilege what is deemed “official” or “important” by dominant cultural standards, often overlooking the everyday materials that make up queer life: bar matchbooks, party flyers, demonstration posters, personal zines. These objects, though small, hold immense historical weight.

In response to these gaps, DIY archiving—through creating and collecting zines, personal ephemera collections, and community-led projects and archives—have long been a way for queer people to preserve our own histories on our own terms. DIY memory-keeping is often nimble, deeply personal, and directly connected to lived experience, while institutional archives with budgets and staffing power can provide long-term preservation and visibility through public programming and outreach. Both approaches matter, and together they can shape a more nuanced queer history.

Queer archives, in all their forms, challenge traditional archival methods by centering the ephemeral, the lived, and the undocumented. They insist that history isn’t just what’s recorded in official records—it’s also in that which lingers after, the gestures, the moments we choose to remember. Whether housed in institutions or tucked away in personal collections, these archives are acts of care and defiance, ensuring that queer lives, in all their complexity, are not erased.

Conclusion: Queer Archival Practice as a Tool for Collective Survival

Queer memory-keeping is not just about preserving the past, but is also about sustaining the present and shaping the future. In times of increasing censorship and erasure, the act of archiving becomes a tool for collective survival. Whether through collecting matchbooks from queer bars, writing zines, documenting personal histories, making memory boxes, or sharing stories within our communities, we refuse disappearance—no matter how hard they try.

You don’t need an institutional affiliation to engage with queer archival practices or to immerse yourself in our histories. Start small—save a flyer from a queer event you attended or performed in, record the names of bars and spaces that hold meaning for you, scan old photos and notes from friends and comrades. Visit and support community archives and tell your friends that they exist and are places for them to explore. Share what you learn from these experiences and pass it on.

Queerness has always thrived in the margins, in the ephemeral, in the moments institutions overlook or dismiss as insignificant. But we know better. We know that our lives, our traces, our everyday moments matter. By documenting them, we refuse erasure. By archiving them, we carve out futures where queerness is not just remembered, but undeniable.

An Archive of Feelings by Ann Cvetkovich [March 2003]

Missouri Republicans threaten to defund public libraries in stunning move over book bans by Alex Woodward [April 12, 2023]

Trump administration dismisses complaints related to book bans By Kanishka Singh [January 24, 2025]

Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity by José Esteban Muñoz [2009]

I still have that Barney Live! In New York City! VHS, too, and think about it fairly often—especially the RIBBON RAIN. That blew my toddler mind. What a production! 🤩💖

This is reminding me of a project I did in undergrad, making a timeline of pre-Stonewall American queer resistance 🥰 The archive fever is real, thank you for all your work, writing, and thoughts!!