Queer Pages! #2 - The Ladder: How Lesbians Built a Print Revolution

Turn to The Ladder, the first nationally distributed lesbian publication in the United States.

Hi Friends,

Welcome back to Queer Pages!, a newsletter series dedicated to the queer and trans periodicals, ephemera, and printed media that documented our movements, built underground networks, and kept radical ideas alive. From activist newsletters and underground newspapers to community flyers and DIY zines, these publications are lifelines, community history, and acts of resistance.

In this edition, we turn to The Ladder, the first nationally distributed lesbian publication in the United States. Published from 1956 to 1972, The Ladder offered connection, validation, and community at a time when being openly lesbian was met with widespread discrimination and erasure. It laid the groundwork for lesbian visibility and activism for generations to come.

Announcements!

If you missed it, be sure to check out the very first Queer Pages! post featuring Gay Flames, one of the bold and radically queer publications to emerge after Stonewall:

Reminder: Black Zine Fair is this Saturday, May 3rd, in Brooklyn, NY! I’ll be dropping by to peruse all of the amazing zines and support all of the talented zinesters (and hopefully trading a few of my own). I’ll be sharing a zine haul soon!

I'm also excited to share that Queer Archive Fever now has paid subscriptions! Becoming a paid subscriber directly supports my work and helps make projects like Queer Pages! more sustainable. If you’d like to support in another way, you can also leave a one-time tip through my Ko-fi! Thank you for being here <3

- Queer Archivist

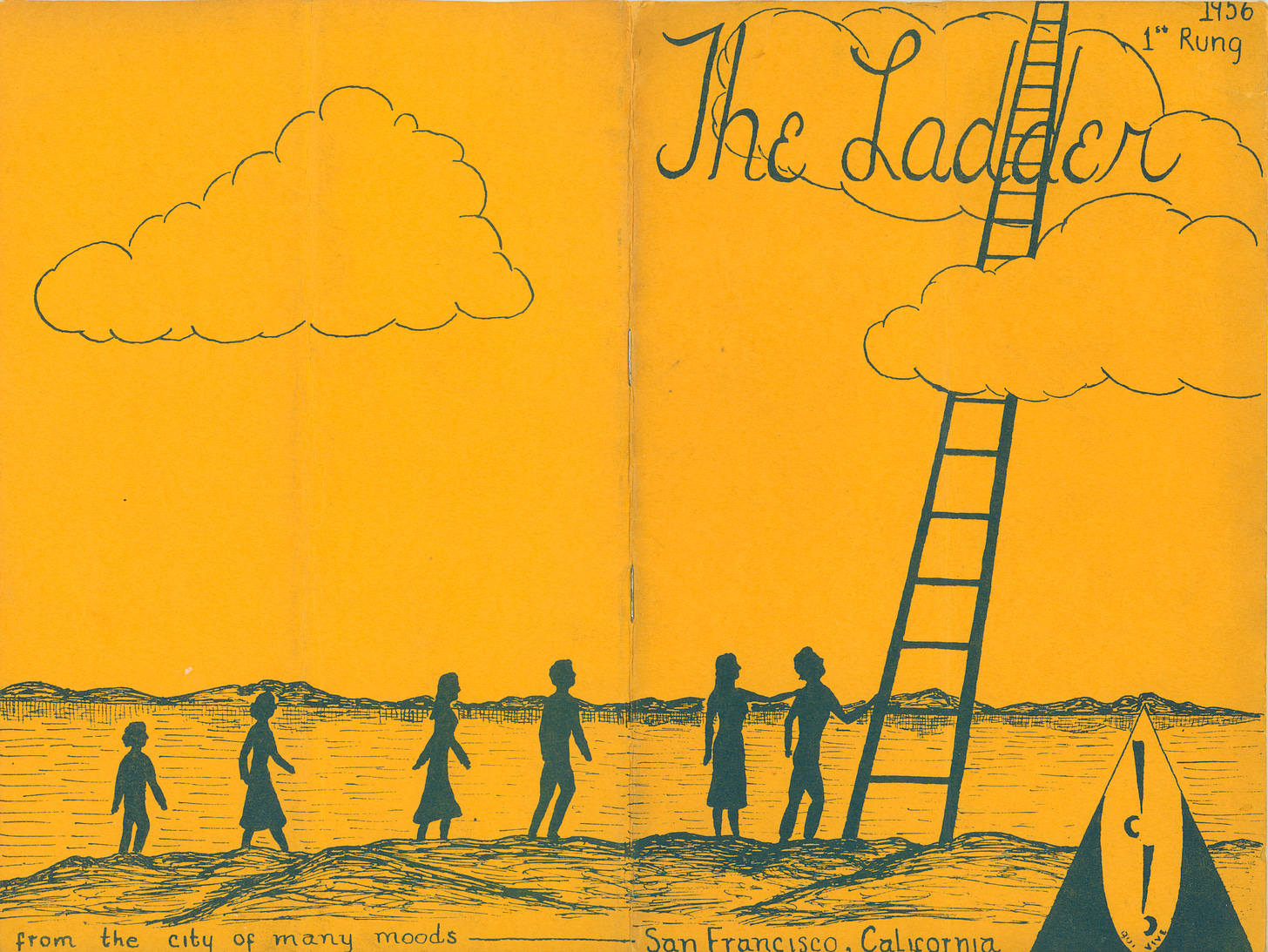

The Birth of The Ladder

“Just one year ago the Daughters of Bilitis was formed. Eight women gathered together with a vague idea that something should be done about the problems of Lesbians, both within their own group and with the public,” reads the opening lines of The Ladder's first issue, published in October 1956. The Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the first lesbian civil rights organization in the U.S., founded in San Francisco in 1955 by Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. Initially imagined as a social club to offer safe activities for lesbians, like picnics, beach trips, and horseback riding, the group soon realized they were building something far more powerful. As discussion deepened, so did their purpose.

Thus, The Ladder was born — a modest DIY magazine circulated discreetly through the mail to protect its readers’ anonymity. The magazine’s title symbolized a means of escape from the “well of loneliness,” a reference to the isolation often associated with lesbian life and popularized by Radclyffe Hall’s famous novel. Membership hovered precariously between six and fifteen women, but their belief in the cause did not waver. In the first issue, they announced:

"This newsletter we hope will be a force in uniting the women in working for the common goal of greater personal and social acceptance and understanding... We offer, however, that so-called 'feminine viewpoint' which [other publications] have had so much difficulty obtaining."

With this mission, The Ladder entered a field dominated by male-led organizations like ONE, Inc. and the Mattachine Society, carving out necessary space for lesbian voices at the time.

Content and Evolution

Early issues of The Ladder featured literary criticism, poetry, letters to the editor, etiquette columns (such as “A Lady is Always a Lady”), short fiction, and updates about social gatherings. The magazine also included book reviews, news, a running bibliography of lesbian literature, and updates from Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) meetings. Contributions often featured essays on notable lesbians and bisexual women throughout history, such as Radclyffe Hall, Queen Christina, and Renée Vivien. The publication also included articles by attorneys, psychiatrists, and doctors, as well as advice columns addressing a range of issues.

Everything was wrapped in a careful, deliberate tone to avoid overt challenges to “decency laws” that could get the group arrested or worse. This approach reflected the assimilationist strategy of the homophile movement, which sought to integrate homosexuals into mainstream society by promoting conformity and respectability.

However, as societal attitudes began to shift in the 1960s, so too did The Ladder. From 1963 to 1966, under the editorial leadership of Barbara Gittings and the bold vision and lens of her partner, photographer and activist Kay Lahusen, the magazine adopted a far more assertive and unapologetic tone. Gittings added the tagline “A Lesbian Review” to the cover, marking a radical embrace of the word lesbian at a time when even naming oneself carried real risk. Together, Gittings and Lahusen revolutionized the magazine’s visual and political language. Lahusen’s photographs introduced readers to real lesbians, marking the first time that lesbian models were publicly named and pictured in an American publication. One of the earliest was Ger van Braam, a lesbian living in Indonesia, who appeared on the cover in 1964 and was the first woman willing to be both named and photographed for The Ladder.

Ger, of Dutch-Indonesian heritage, had previously contributed to The Ladder with her short story "A Dope" in August 1963. Her subsequent correspondence with Gittings provided profound insights into the challenges faced by lesbians in Indonesia, including societal pressures to marry and the pervasive sense of isolation. Despite these obstacles, Ger's courage in sharing her story and image helped bridge geographical divides, fostering a sense of global solidarity among lesbians. Her contributions not only enriched the magazine's content but also symbolized a bold step toward visibility and representation.

Gittings understood that visibility was not just symbolic. At a time when many lesbians risked losing their jobs, their families, and their safety if they were exposed, choosing to show a real face, a real name, was a radical act of defiance. Through her leadership, The Ladder shifted from coded respectability toward proud self-recognition, inviting readers to imagine a future where they no longer had to live in hiding. Gittings famously stated:

“I wanted readers to see lesbians as real people — not as shadows or secrets.”

This growing boldness sparked both inspiration and division. Some within DOB feared that too radical a tone might provoke dangerous backlash, while others believed bolder visibility was urgently needed. Tensions around the magazine’s vision and voice would continue to shape its evolution, especially as new voices and broader political movements began to influence its pages.

Ernestine Eckstein and Expanding the Vision of The Ladder

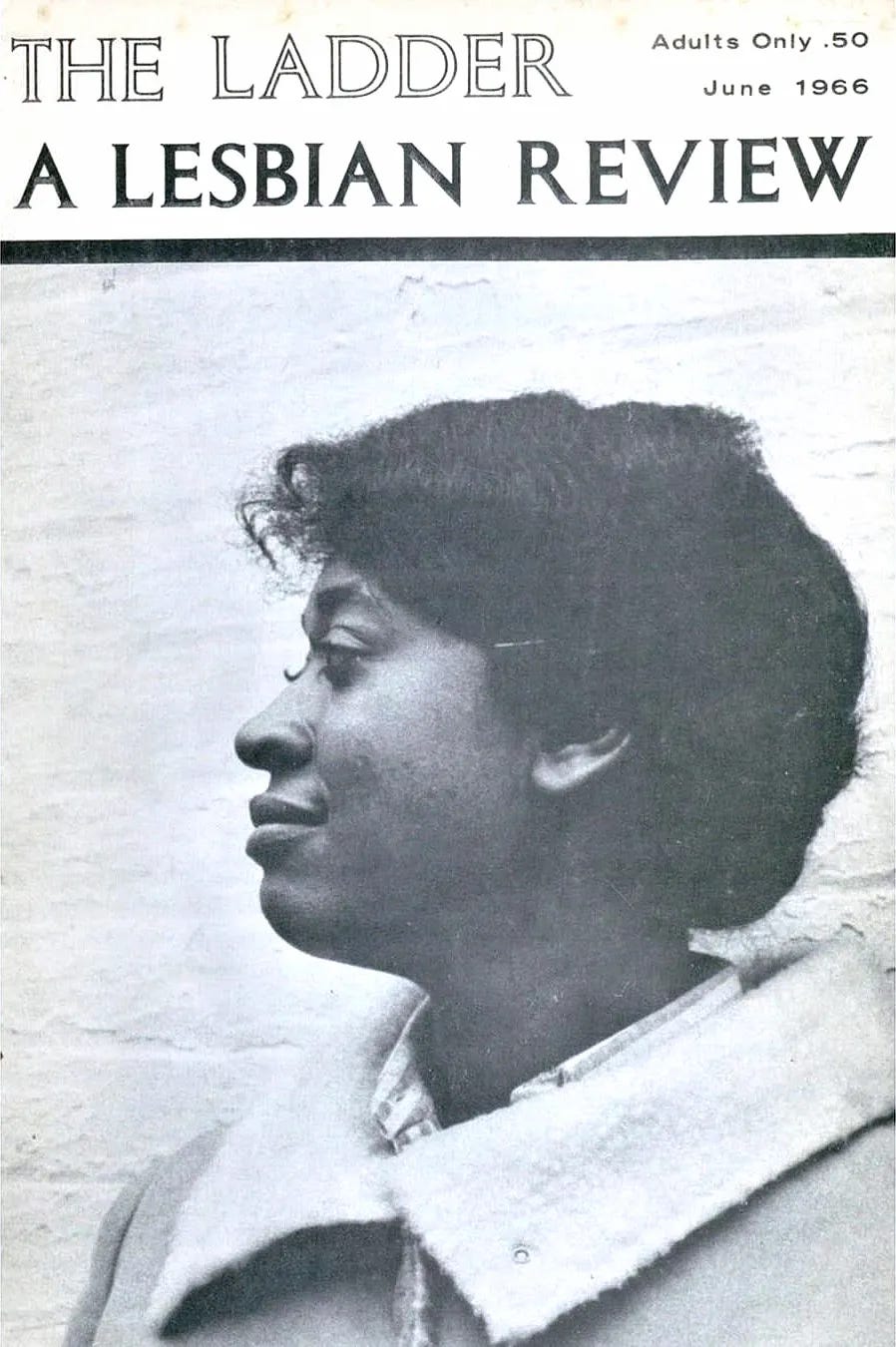

In June 1966, The Ladder published a groundbreaking interview with Ernestine Eckstein, one of only two women of color ever featured on its cover and the first Black woman on the cover. Eckstein, a Black lesbian activist deeply influenced by the Civil Rights Movement, used her interview to advocate for public demonstrations, coalition-building, and a broader, more intersectional vision of lesbian activism. Her appearance in The Ladder disrupted narrow ideas about who made up the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) and pushed the magazine—and the movement—toward a more inclusive future.

Eckstein’s words carried the weight of experience: she had participated in Black civil rights protests as a member of the NAACP before becoming vice president of the DOB's New York chapter. "Picketing I regard as almost a conservative act now," she explained in the interview, arguing that visibility and action were crucial for homosexuals just as they had been for Black Americans.

Today, Eckstein’s interview remains one of the few substantial records of her activism. In more recent years, the Making Gay History podcast uncovered even more about her story, locating the complete original recording of her 1965 interview with Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen. In it, Eckstein spoke about the need for coalition across marginalized communities, insisting that the fight for lesbian rights could not be separated from broader struggles for racial and economic justice. Her ideas and praxis were far ahead of her time, anticipating the intersectional frameworks that would only formally emerge decades later. Through Eckstein, The Ladder made a bold, forward-looking statement about the future of the homophile movement—one that embraced difference, demanded visibility, and called for solidarity across identities.

Impact and Legacy

The Ladder played a crucial role in fostering a sense of community among lesbians across the country, providing a forum for discussion, support, and activism at a time when few other public platforms existed. Its influence rippled outward, inspiring new LGBTQ+ organizations, publications, and grassroots networks.

Tensions around The Ladder's direction, combined with the ever-present financial strain of running a lesbian publication with a small subscription base and limited access to mainstream distribution, eventually contributed to the organization’s fragmentation and The Ladder eventually ceased publication in 1972.

The Ladder planted seeds that blossomed in the rise of lesbian feminist presses, the explosion of LGBTQ+ newspapers and magazines in the 1970s, and the growing visibility of lesbians within broader liberation movements.

Sources + Further Reading:

For those interested in exploring more about The Ladder and it’s history, here are some of the sources that informed this post:

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project – Picket at the Great Hall, Cooper Union, Second-Ever U.S. Gay Rights Protest

Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context, edited by Vern L. Bullough

Making Gay History Podcast – Barbara Gittings & Kay Lahusen Episode

Making Gay History Podcast - Ernestine Eckstein Episode

Queer Indonesian Archive - Letters from Ger: An exhibition exploring the life of Ger van Braam

Lesbian Herstory Archives – The Ladder Collection (Periodicals, Newsletters & Zines)

Wikipedia – The Ladder (magazine)

This is such a great article on the evolution and impact of this lesbian newsletter. This series makes me want to start a queer zine every time.

I’m not sure if you’ve answered this in a previous article, but do you work at a queer focused archive or do you work in a more general repository and focus on queer records? Obviously, feel free to not answer that for privacy reasons.

I’m an archivist at a historical society in the Midwest and I’m a bit jealous of the work you get to do. We have verrrry few materials on the queer community in our city as there’s another archive that specializes in that and I just process collection after collection of rich old straight guys.

Great article! For further reading, there’s also a wonderful book about the DOB called “Different Daughters” by Marcia Gallo. https://burningbooks.com/products/different-daughters-a-history-of-the-daughters-of-bilitis-and-the-rise-of-the-lesbian-rights-movement?srsltid=AfmBOopXLxOY0VCeRFiN6Cf6qjdRFG7oerJm8FhfNE85lAukHHFGpolO