Queer Pages! #1 - Gay Flames: Igniting the Homofire Movement

Celebrating the legacy of Gay Flames

Hi Friends,

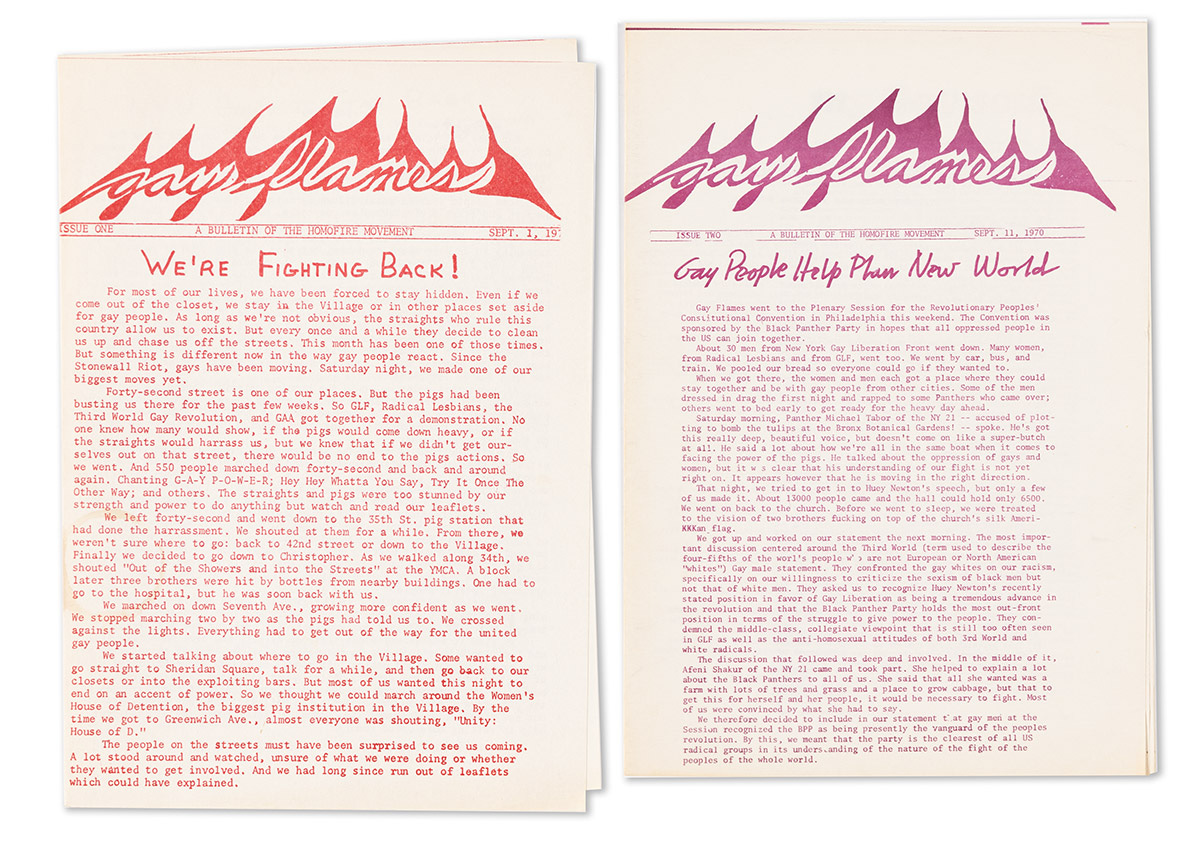

Welcome to the very first Queer Pages!, a newsletter series dedicated to the queer and trans periodicals, ephemera and printed media that documented our movements, built underground networks, and kept radical ideas in circulation. From activist newsletters and underground newspapers to community event flyers and DIY zines, these publications are lifelines, community history, and acts of resistance.

Queer Pages! explores the histories of these publications, the people behind them, and the ways they continue to inspire resistance and storytelling today. This first issue dives into Gay Flames, one of the boldest radical queer publications to emerge after Stonewall, capturing the energy of a movement refusing to be silenced. Subscribe to be notified about news Queer Pages! posts.

I’d also like to share that I’ve launched a Ko-fi page to help sustain Queer Archive Fever! If you love what I do and want to support independent queer archival research, a small contribution helps keep this newsletter going.

Thank you for being here and for valuing queer history. I hope you enjoy this first issue of Queer Pages!

- Queer Archivist

“For most of our lives, we have been forced to stay hidden. Even if we come out of the closet, we stay in the Village or in other places set aside for gay people. As long as we’re not obvious, the straights who rule this country allow us to exist. But every once in a while they decide to clean us up and chase us off the streets. This month has been one of those times. But something is different now in the way people react. Since the Stonewall Riot, gays have been moving. Saturday night, we made one of our biggest moves yet.”

These opening lines from the premiere issue of Gay Flames captures the fervor of a burgeoning movement. In the aftermath of the Stonewall Riot, the early 1970s saw a surge in LGBTQ+ activism, with grassroots publications playing a pivotal role in mobilizing the community. Among these was Gay Flames: A Bulletin of the Homofire Movement, a radical self-published pamphlet series that emerged in New York City in 1970. Let's delve into the origins and impact of this radical queer publication.

Taking the Streets, Building Power!

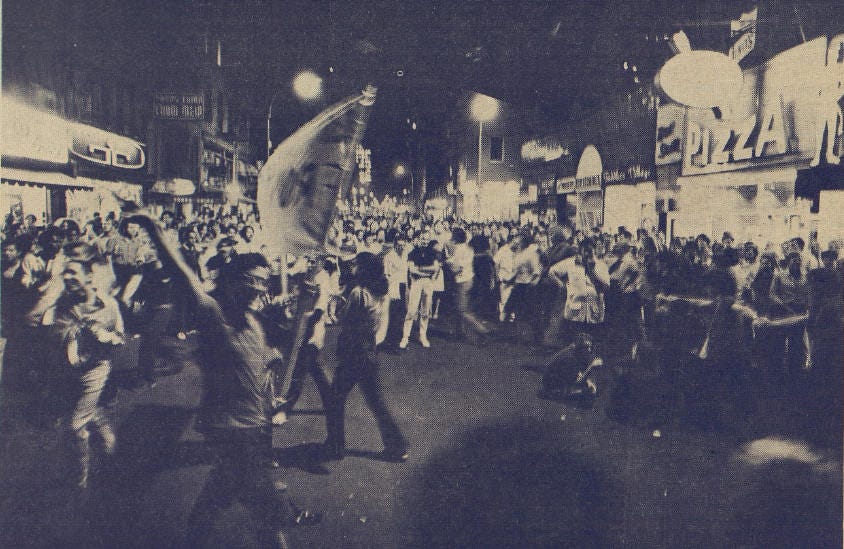

The Premier Issue of Gay Flames opens with a vivid account of a particularly significant queer demonstration on 42nd Street in 1970. They write:

“No one knew how many would show, if the pigs would come down heavy, or if the straights would harass us... 550 people marched down forty-second and back and around again. Chanting G-A-Y P-O-W-E-R; Hey Hey What Do You Say, Try It Once The Other Way..."

It is clear through this excerpt that this wasn’t a spontaneous demonstration but a coordinated display of resistance:

“So GLF [Gay Liberation Front], Radicalesbians, the Third World Gay Revolution, and GAA [Gay Activist Alliance] got together for a demonstration…”

The demonstration moved beyond 42nd Street, with protesters marching to the 14th Police Precinct on West 35th Street to demand the release of those arrested earlier that night. From there, they continued down Seventh Avenue toward Greenwich Village, stopping at the Women’s House of Detention, where the crowd grew to nearly 1,000. The people detained inside responded by shouting through the barred windows and throwing burning objects into the streets in solidarity.

As the protest reached Sheridan Square, it coincided with a police raid on The Haven, a queer nightclub at 1 Sheridan Square, escalating into direct confrontations. Some GAA members withdrew, but others stayed as the demonstration turned into a riot. Police responded with force, leading to fires, overturned cars, shattered storefronts, and multiple injuries. Twelve people were arrested.

The message was clear: queer people were done hiding and were ready and willing to resist the constant attacks on our communities.

Unlike Stonewall, which was a spontaneous uprising against relentless police brutality, this march was intentional, strategic, and a signal that queer people were organizing in new ways.

Campus Activism at NYU: The Weinstein Hall Occupation

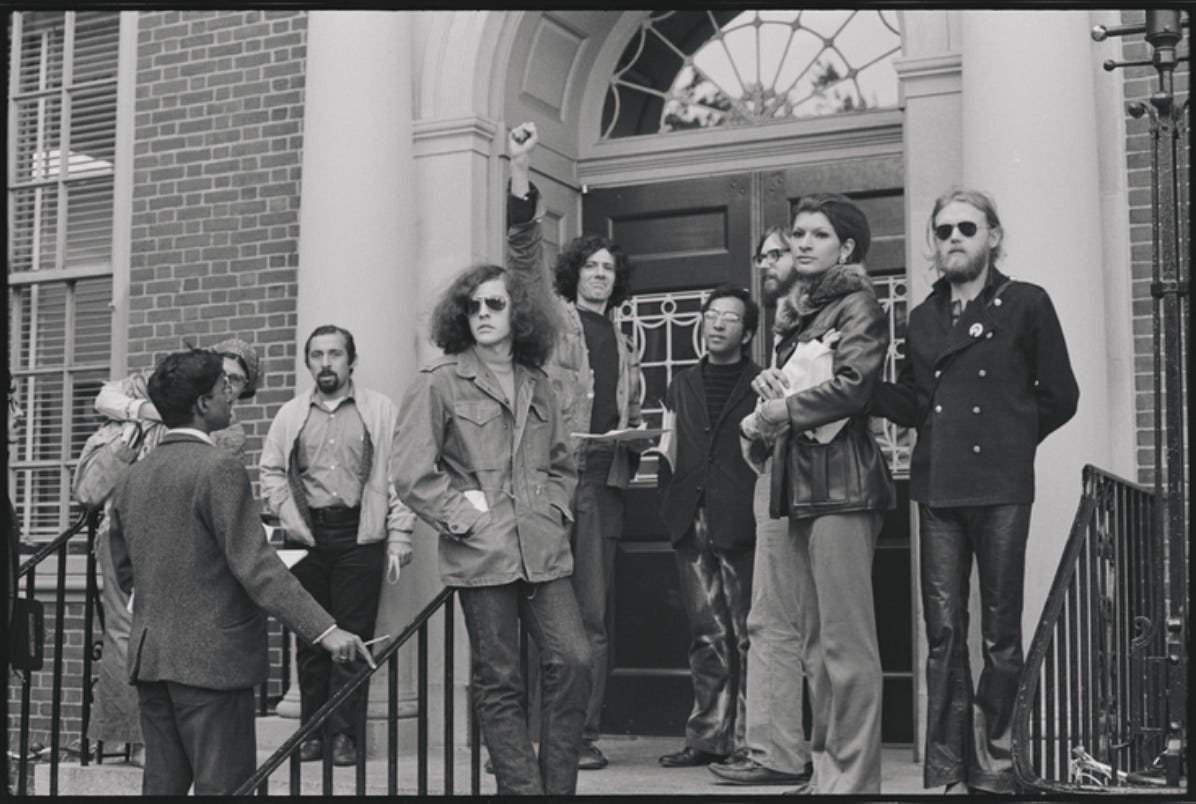

Gay Flames Issue 1 also detailed activism at NYU, where queer students and organizers pushed back against institutional homophobia. One of the most significant moments was the Weinstein Hall occupation in September 1970, a five-day sit-in protesting NYU’s abrupt cancellation of gay dances. The university claimed it was a logistical issue, but activists saw it as an attempt to shut down a space that was becoming a refuge for queer people.

In response, the NYU group Gay Student Liberation called for an immediate occupation of Weinstein Hall. A liaison was sent to a Gay Liberation Front meeting to request additional volunteers, and within hours, nearly 70 people had gathered in the hall. Among them were Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, both seasoned activists who had been on the frontlines of the movement long before the term “gay liberation” entered mainstream discourse. The occupation remained open, with activists coming and going, meeting with students, handing out fliers around the university, and holding public teach-ins on gay liberation. Student representatives voted to support the strike, offering blankets to occupiers while the administration attempted to freeze them out by turning up the air-conditioning.

Sylvia Rivera later reflected on the significance of the Weinstein Hall occupation and its lasting impact on trans and queer organizing in Queens in Exile: The Forgotten Ones, she recalled:

“…STAR was born after a sit-in we had at New York University with the Gay Liberation Front. We took over Weinstein Hall for three days. It happened when there had been several gay dances there, and all of a sudden the plug was pulled because the rich families were offended that queers and dykes were having dances and their impressionable children were going to be harmed.

So we ended up taking that place over. That’s another piece of history that is very seldom told even in regular gay history about that sit-in. Maybe that’s because it was the Street Queens once again. STAR House was born out of the Weinstein Hall demonstration because there were so many of us living together.”

The occupation challenged the ways institutions policed and controlled LGBTQ+ life. It also revealed divisions within the movement, showing who was willing to fight for all queer people. The violent police raid that ended the occupation reinforced what many already knew. Queer and trans people, particularly those at the margins, had to build their own structures of support and resistance. In the months that followed, Rivera and Johnson founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), a grassroots organization dedicated to protecting trans people of color and unhoused queer youth. STAR provided shelter, support, and advocacy, creating one of the first trans-led activist spaces of its kind.

By documenting these events, Gay Flames preserved the memory of an action that mainstream historical accounts have often overlooked. The sit-in at Weinstein Hall was not just about a canceled dance. It was about demanding space, refusing erasure, and taking action when institutions attempt to erase us and our spaces.

Race, Coalitions, and Conflicts in the Gay Liberation Movement

Gay Flames Issue 2 captures a complex moment in early gay liberation activism, documenting New York gay, lesbian and queer activists’ participation in the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention (RPCC), organized by the Black Panther Party in September 1970. The convention aimed to draft a new constitution centered on those oppressed by capitalism, white supremacy, and state violence. Radical organizations like the Young Lords, Third World Gay Revolution, Radicalesbians and Gay Liberation Front (GLF) were in attendance alongside Black activists, feminists, and leftists from across the country.

For some white gay activists, this was an opportunity to align their struggle against homophobia with broader liberation movements. However, tensions emerged. Black and Brown queer activists had to fight for recognition within both their own organizations and broader radical spaces, where issues of gender and sexuality were often sidelined.

Discussions between some members of the GLF and Third World Gay Revolution exposed deep tensions around race and privilege in the gay liberation movement. Black and Brown queer activists challenged their white comrades for failing to recognize their own racial biases and for being more willing to critique the sexism of Black men than that of white men. As Gay Flames reported, Third World gay activists confronted white members of the GLF directly:

“They confronted the gay whites on our racism, specifically on our willingness to criticize the sexism of black men but not that of white men. They asked us to recognize Huey Newton’s recently stated position in favor of Gay Liberation as being a tremendous advance in the revolution…”

These moments of reckoning forced some white gay activists to acknowledge their own limitations, while also highlighting the growing push for an coalitional approach to liberation. Just weeks before the RPCC, Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, issued a groundbreaking statement of solidarity in The Black Panther newspaper:

“We must gain security in ourselves and therefore have respect and feelings for all oppressed people. We must relate to the homosexual movement because it is part of us… They might be the most oppressed people in society.”

Newton's call for unity was groundbreaking, marking one of the first instances where a prominent Black political organization extended support to gay liberation. This letter was widely circulated and reprinted by feminist and gay activists, solidifying the inclusion of these groups at the RPCC.

His message was also later featured in the Gay Flames, specifically in pamphlet No. 7 titled "3rd World Gay Revolution." By contributing to this pamphlet, Newton emphasized the importance of coalition-building across marginalized communities and set an example for how it could be done.

The Gay Flames coverage of the RPCC offers a glimpse into a movement attempting to navigate these contradictions. It wasn’t a seamless merging of struggles, and it certainly wasn’t a moment of pure solidarity. But it was a moment of confrontation—between movements, between ideologies, and between the fractures within liberation politics itself.

Legacy and Preservation

The enduring impact of Gay Flames can be traced through its twelve issues, which ran from 1970 to 1971, with the final issue released in March 1971. The publication played an essential role in documenting and shaping the early gay liberation movement, offering both a platform for queer voices and a call for radical change. One of its defining features was its unapologetic stance in advocating for a gay identity that was distinct from societal norms. Through articles, interviews, and manifestos, Gay Flames articulated the desire for self-determination, empowerment, and, most significantly, the creation of a uniquely gay culture.

In a broader historical context, Gay Flames represented the fierce and unwavering activism of the time, serving as an essential piece in the mosaic of queer radical politics that began to emerge in the wake of the Stonewall Uprising. The magazine captured the voices of a diverse range of individuals, transgender activists, people of color, working-class queers, whose struggles were often marginalized within the more mainstream gay rights movement. By foregrounding these voices, Gay Flames not only chronicled the battles of the past but also charted a course for future generations to continue fighting for justice and equality.

Today, original copies of Gay Flames are housed in several important archival collections, including the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, the William Way LGBTQ+ Community Center in Philadelphia, and special collections at various universities. Additionally, fully digitized versions of Gay Flames are available through JSTOR.

These archives preserve not just the physical copies but also the radical, revolutionary spirit that fueled their creation. As a historical document, Gay Flames remains a testament to the resilience of the LGBTQ+ community, and its preservation ensures that the vibrant, complex history of the early gay liberation movement will continue to inspire future generations.

Through these efforts, the radical queer politics of the early '70s remain a vital part of our collective memory, a reminder that the fight for liberation is ongoing and that the work of activists like those behind Gay Flames, and documented on its pages, laid the foundation for where we are today and provide us with the tools to keep resisting the systems that aim to harm and erase us. There is immense power in looking back at the past, learning from it, and drawing inspiration to fuel our movements today.

Queer Pages! celebrates the legacy of Gay Flames, acknowledging its role in fanning the flames of liberation and inspiring future generations to continue the fight for liberation.

Sources:

Loved this piece! Gay Flames is such a powerful image and so clever. It’s amazing how much groundwork has been laid for us by our queer elders. It’s a blessing to be able to have access to these texts for free. It gives me a lot of hope for the future.

Highly suggest you check out Thing originally a zine focused on the Black queer House music scene in the 1980s, now preserving that legacy and bringing Black queer culture. https://houseofthing.com/